It may be recalled that the RBI’s Financial Stability Report of December 2021 had called attention to the retail credit growth model confronting headwinds

The ‘buy now, pay later’ (BNPL) game is set for a big change. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has sought details of shadow banks’ BNPL arrangements with e-commerce (e-com) players

The central bank has also asked for information on their roles as transferor or transferee for loans under its “Master Direction on Transfer of Loan Exposures”, issued on September 24, 2021. The urgency of the issue was evidenced in the RBI’s email to nonbanking financial companies (NBFCs) on Monday: That the data is to be submitted by the end of the day. Senior officials in NBFCs and the BNPL universe are unanimous that “the RBI appears to have taken the first steps towards sizing up this market, and usher in stricter regulations”, and also “ring in transparency to the growing BNPL segment within the wider retail consumer finance”.

The aggregate loans given via the BNPL route are not known though the “Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending including Lending through Online Platforms and Mobile Apps” in November last year gave a sense of it.

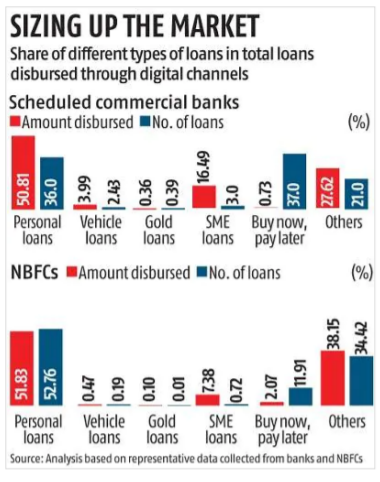

It noted that “even though the amount disbursed under BNPL schemes is only 0.73 per cent (banks) and 2.07 per cent (NBFCs) of the total loans disbursed, the volumes (number of loans) are quite significant”.

In digital lending (and not restricted to BNPL), disbursements by RBI-sampled entities exhibited a more than 12-fold increase to Rs1,41,821 crore in FY20 from Rs 11,671 crore in FY17.

In FY17, there was not much difference between banks (0.31 per cent) and NBFCs (0.55 per cent) in terms of the share in the amount of loans disbursed digitally whereas NBFCs were lagging in terms of the number of loans with a share of 0.68 per cent vis-à-vis 1.43 per cent for banks.

Since then, NBFCs have taken great strides in lending through digital mode.

In a related pincer-move, it has been learnt that the banking regulator may standardise the way first-loss default guarantees (FLDGs) — extended by lenders of all hues — are structured. An FLDG is the amount offered by digital platforms (or any other unregulated entities) as guarantee to lenders on whose behalf they source business. This is to protect lenders when loans go bad.

The issue here is that norms for issuing FLDGs are not standardised. Many are issued by unregulated entities which are not credit-rated and basically ride on private equity capital.

If lenders – be it NBFCs or banks — were to give loans taking comfort from such nonstandardised FLDGs, they will take a hit in a situation if it can’t be invoked. Simply put, FLDGs are another version of credit guarantees. “It may well be that the RBI may insist that only entities regulated by it can issue FLDGs,” said a top source.

On the product side, given the interest-free nature of BNPL schemes, such exposures are not reported to credit bureaus because “they don’t fall under the definition of ‘credit’”.

The RBI Working Group had noted “it is often labelled as a product for enhanced customer engagement and seamless user-experience, a potential replacement for credit cards, but not a credit product”. Industry sources pointed out even when the exposure was later converted into equated monthly instalments (EMIs), NBFCs would show it as a fresh loan — prudent accounting has to show it as a dud-loan. As for all practical purposes, the customer had failed to honour the original terms of the BNPL e contract.

“These are grey areas, and need to be fleshed out,” said another source, “given that NBFCs are on Ind-AS with its ‘expected-credit loss’ provisioning norms”

Another area is pricing. While customers are happy to avail themselves of BNPL schemes, given their interest-free nature riding on the back of subventions from manufacturers, failure to make good the payment during the interest-free period attracts hefty penalties and fees. This brings the Usurious Loans Act (1918) into effect. Under the Act, courts can examine and re-open transactions if there is reason to believe that the interest rate is excessive, or a transaction is substantially unfair. The Act was enacted in the pre-Independence era to offer protection to agrarian borrowers who were often charged excessively high interest rates. But Section 21A of the Banking Regulation Act (1949) limits the

application of the Act to banks.

It may be recalled that the RBI’s Financial Stability Report of December 2021 had called attention to the retail credit growth model confronting headwinds: Delinquencies have risen; and the new-to-credit segment is showing a dip in originations. It referred to the Bank for International Settlements’ observation that in emerging markets, bad loans “typically peak six to eight quarters after the onset of a severe recession”.

Source Link :